Managing carbapenem-resistant gram-negative infections: Challenges in the developing world

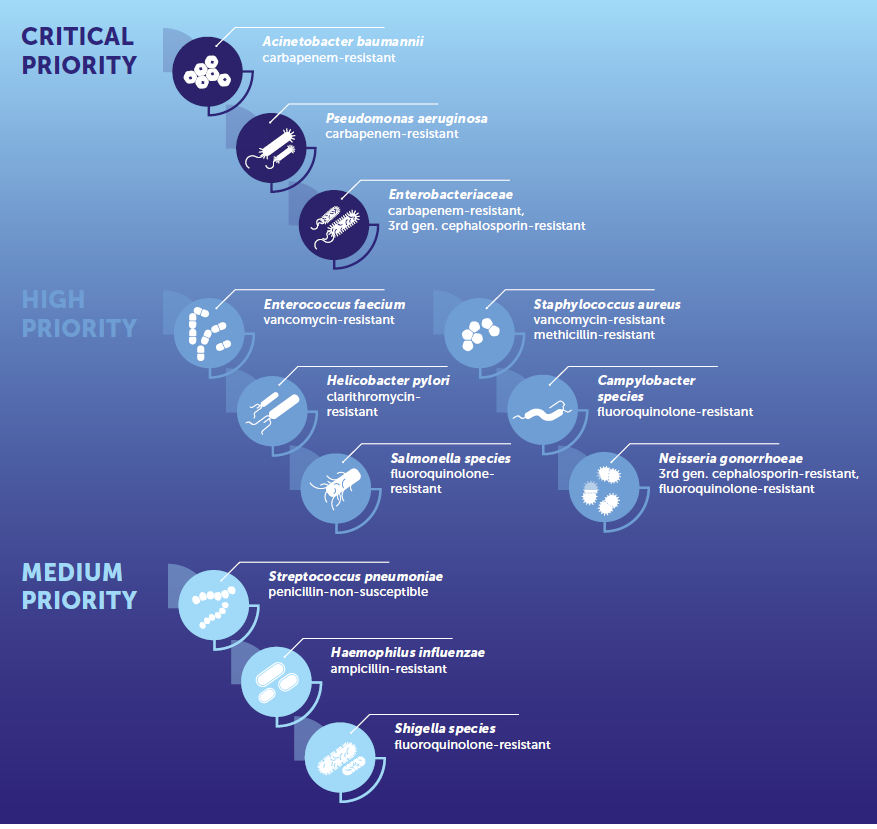

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email Developing countries face innumerable challenges in the management of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative organisms. The World Health Organization lists carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae as critical priority pathogens that are in urgent need of new antibiotics. CRE, CRPA and CRAB account for 5% to 15%, 30% to 50% and > 50% of respective isolates in developing nations. (1) These rates are twice those seen in the developed world. Having done an ID fellowship in India and now currently completing one in the U.S., I've come to appreciate how the problems in each setting are different.

Developing countries face innumerable challenges in the management of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative organisms. The World Health Organization lists carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae as critical priority pathogens that are in urgent need of new antibiotics. CRE, CRPA and CRAB account for 5% to 15%, 30% to 50% and > 50% of respective isolates in developing nations. (1) These rates are twice those seen in the developed world. Having done an ID fellowship in India and now currently completing one in the U.S., I've come to appreciate how the problems in each setting are different.

Polymyxin-based therapy: Combination therapy or monotherapy?

In developing countries, treatment of carbapenem-resistant organisms is largely polymyxin-based, typically in combination with other agents. While there has been literature challenging combination therapy by demonstrating noninferiority of polymyxin monotherapy, noninferiority of monotherapy may be affected by dosing issues related to the carbapenem combined with polymyxin. In these studies, the MIC of 90% of isolates for carbapenem was > 8 mcg/ml. The dose of meropenem used was 1 gram every 8 hours as a 30-minute infusion. However, combination is recommended only when the carbapenem MIC is < 8 mcg/ml and should be given at a dose of 2 grams every 8 hours as a prolonged infusion over 4 hours. The results of these studies are mostly driven by CRAB, but CRPA and CRE were underrepresented. Trials reported numerical reductions in 28-day mortality with combination therapy compared with colistin alone for CRPA and CRE, which may need to be explored specifically. (2,3)

Challenges with polymyxin-based therapies: Why is there a need to move toward newer drugs?

Polymyxin-based therapy is not without challenges. Most gram-negative bacilli have MICs < 2 mcg/ml for colistin. For therapeutic efficacy, colistin must be dosed to reach a steady state concentration of 2 mcg/ml. In those with normally functioning kidneys, the steady state concentration cannot be achieved due to rapid clearance of the drug. Moreover, colistin also poorly concentrates in the lung, thus affecting efficacy. (4) It is not possible to increase the dose as most patients develop acute kidney injury at a trough concentration of > 2.2 mcg/ml. (5) Predominant infections in the AIDA and OVERCOME trials were pneumonia, in which mortality rates of up to 50% were observed when polymyxin-based therapy was used. (2, 3) The situation is made even worse by the discovery of transmissible polymyxin resistance in the form of the MCR-1 gene. Based on these findings, while it is recommended to move away from polymyxin-based therapy towards newer beta-lactams/beta-lactamase inhibitors, it may not always be possible for the reasons discussed below.

Are newer BLs/BLIs the ultimate solution?

Newer BLs/BLIs, including meropenem-vaborbactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, imipenem-relebactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam, have been a great addition to the armamentarium as colistin-sparing strategies in combating carbapenem-resistant gram-negative infections. It is true that high cost and limited availability are barriers to its widespread use in developing countries. But more importantly, the epidemiology of resistance mechanisms driving carbapenem resistance is much different, limiting their utility.

Challenges in CRE

The common carbapenem resistance mechanism among CRE in Western countries is mediated largely by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase and to some extent by OXA-48. Meropenem-vaborbactam and ceftazidime-avibactam are excellent choices of newer BLs/BLIs for treating these infections. However, in South and Southeast Asian countries, carbapenem resistance is mostly due to metallo beta-lactamases like NDM for which the above antibiotics will not work and requires a combination of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam after testing for synergy. (6) The problem gets worse when there is a PBP3 insert, which has the potential to burn down all good regimens as avibactam cannot protect aztreonam from hydrolysis and also potentially cefepime-zidebactam may not work. (7)

Challenges in CRPA

The issue is similar with CRPA. While ceftolozane-tazobactam is a great choice of antibiotic for efflux pump mediated carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa, it is not true for isolates from developing countries, where resistance is mainly due to MBLs in combination with mutation in efflux pump and porin channels. (8)

Challenges in CRAB

The situation gets even more complicated with CRAB. Major carbapenem resistance mechanisms are due to non-OXA-48 and MBLs. (6) Ceftazidime-avibactam will not work against non-OXA-48, and the combination of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam will not work against MBLs due to the intrinsic resistance of Acinetobacter to aztreonam. We may jump to the conclusion that cefiderocol is the ultimate answer, but this is only partially true. Post hoc analysis by the pathogen in the CREDIBLE CR trial showed a numerical increase in mortality for CRAB treated with cefiderocol possibly due to heteroresistance. (9) Like all other newer BL/BLIs, resistance to cefiderocol can develop on therapy when used alone, and combination strategies might have to be explored.

Conclusion

While producing newer antimicrobials and newer BL/BLI combinations like cefepime/taniborbactam and sulbactam-durlobactam to treat these infections may seem to be the way forward, we may need to relook at newer options like bacteriophage therapy to combat this issue. It is also important to recognize that the problem of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries has been fueled, in part, by unregulated “over the counter” availability of restricted antibiotics, indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in hospitals and lack of infection control practices including isolation and contact precautions. An efficient antimicrobial stewardship program and a strict hospital infection practice may go a long way in controlling this evolving pandemic of gram-negative resistance.

Image credit: Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017(WHO/EMP/IAU/2017.12). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Figure appears on page 79 (fig. 23).

References

- Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EMP-IAU-2017.12.

- Kaye Keith S., Marchaim Dror, Thamlikitkul Visanu, et al. Colistin Monotherapy versus Combination Therapy for Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms. NEJM Evidence 2022; 2: EVIDoa2200131.

- Paul M, Daikos GL, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2018; 18: 391–400.

- Gurjar M. Colistin for lung infection: an update. Journal of Intensive Care 2015; 3: 3.

- Nation RL, Rigatto MHP, Falci DR, et al. Polymyxin Acute Kidney Injury: Dosing and Other Strategies to Reduce Toxicity. Antibiotics; 8. Epub ahead of print 2019. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics8010024.

- Nordmann P, Poirel L. Epidemiology and Diagnostics of Carbapenem Resistance in Gram-negative Bacteria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019; 69: S521–S528.

- Devanga Ragupathi NK, Vasudevan K, Muthuirulandi Sethuvel DP, et al. Novel PBP3 insertions in MDR Escherichia coli from blood stream infections: A threat for newer β-Lactam combinations. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020; 101: 114.

- Yoon E-J, Jeong SH. Mobile Carbapenemase Genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Frontiers in Microbiology; 12, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.614058 (2021).

- Bassetti M, Echols R, Matsunaga Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021; 21: 226–240.