“Do you have the COVID-19 vaccines here with you today?” was a question I received from a community member during a vaccine education session in San Bernardino, California, in September 2023. Sadly, I had to inform the congregant that I did not have the vaccines on hand as a previous vaccinating partner had recently jilted me.

“Do you have the COVID-19 vaccines here with you today?” was a question I received from a community member during a vaccine education session in San Bernardino, California, in September 2023. Sadly, I had to inform the congregant that I did not have the vaccines on hand as a previous vaccinating partner had recently jilted me.

This question marked a turning point in my three-year journey to promote vaccine uptake within Black communities in San Bernardino County. Gone were the questions heavily riddled with vaccine mistrust and weariness, and in their place was the intent to be immunized. This brings forth a harsh reality: We cannot address trustworthiness without addressing the ever-present accessibility barriers to preventative health across minoritized populations in the United States.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, racially and ethnically minoritized individuals had significantly higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death compared to their non-Hispanic White Counterparts. (1,2) Despite these detrimental outcomes, at Loma Linda University — which housed the largest mass vaccination clinic site in San Bernardino County — low rates of Black individuals were represented among clinic vaccinees. (3) This mirrored the decreased vaccine uptake across Black communities nationwide, which was heavily attributed to vaccine hesitancy mediated by mistrust of the U.S. health care system due to decades of mistreatment and systemic oppression. (4,5) To a lesser degree, limitations in vaccine accessibility were also cited as a critical factor in lower COVID-19 immunization rates. (2)

Collaborating with faith-based groups

Noting these contributing factors to low vaccine uptake across the Black population, I worked collaboratively with faith-based organizations (the Inland Empire of Concerned African American Churches and the Congregations Organized for Prophetic Engagement) in San Bernardino County to develop a community-academic partnership that had a primary goal of restoring trust in preventative therapeutics and providing immunizations in an easily accessible forum (free of cost, no digital sign-up and minimal transportation required). (3) The partnership uses a three-tiered approach to address vaccination barriers, including engaging additional Black faith leaders (tier 1), giving vaccine education (tier 2) and providing immunizations in low-barrier community vaccination clinics (tier 3). (3)

The use of the approach has resulted in the provision of more than 3,600 vaccine doses and 15 educational sessions attended by more than 300 individuals cumulatively. (6) More importantly, there has been a notable change in vaccine acceptance as the tiered approach has been used to encourage immunization uptake for other preventable diseases. Nonetheless, there has also been a consistent evolution in the format in which the vaccinations have been provided through our community clinics, with each iteration of change apparent to the community members.

At the start of the collaboration, in February 2021, I would transport the vaccines to each community clinic, and under my direct preceptorship, pharmacy and medical students would lead the vaccination of the community members. As a racially concordant provider and the education messenger, my presence at each step of the community’s vaccination process needed to be evident. However, in February 2022, the support I had previously been provided began to dwindle as the urgency surrounding the pandemic began to wane.

With this, I was left to manage all vaccination tasks independently, severely limiting the number of vaccines our team could offer during each clinic. Since many of the community members had become reliant on this mode of vaccination, finding a vaccinating partner to manage all related tasks became critical. In November of 2022, I secured a vaccinating partner, and while the community members noted my absence as a vaccinator, we continued to immunize 20 to 30 individuals per clinic.

The loss of public funding and its impact

The loss of public funding and its impact

In 2023, the elimination of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency order declared under section 319 of the Public Health Service Act — and the commercialization of the COVID-19 vaccines — marked an additional change in the vaccination processes of the community clinics. (7) The PHE ensured that COVID-19 vaccines and treatments were distributed free of charge to the public. (7) Also, many community vaccine outreach efforts were encouraged and funded through award programs created in response to the PHE; its elimination resulted in the cessation of these programs. (8)

With public funding no longer available, our vaccinating partner withdrew their participation, and from May to October of 2023, I searched tirelessly for an alternative to fill the gap. I explored becoming an independent vaccinator approved by the state of California, and I emailed vaccine companies to ask for vaccine donations with no success. Despite receiving funding to complete the educational sessions from August to December 2023, the community was incredibly vocal about their disappointment in the lack of vaccine availability at the clinics.

Through a last Hail Mary request, the San Bernadino Department of Public Health joined as our community vaccinating partner in late October 2023 and began providing vaccinations at the community clinics. From October to December 2023, we gave 96 vaccine doses (40 influenza and 56 COVID-19 vaccinations). While we were able to vaccinate vulnerable community members, I can’t help but think about the additional number of individuals who could have been further protected against COVID-19 had we had a vaccinating partner at the start of the intervention. I also consider the number of lives that could have been impacted if the programs that provided hope during the peak of the pandemic had continued to receive designated funding.

Sadly, four years into the pandemic, the rates of COVID-19–related deaths continue to be disproportionately high across the U.S. Black population. (9) Unfortunately, the elimination of the PHE limits the completeness of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 vaccine administration tracking data. (10) Nevertheless, survey reports indicate that less than 50% of the U.S. adult population has received an updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine. (10)

In California, only 10.8% of Black/African American individuals are up to date on their COVID-19 vaccination. (11) While this could be related to several factors, it should also be noted that high rates of minoritized individuals in California are uninsured, which may contribute to the low vaccine uptake. (12) Despite the continued coverage of the vaccines through the PREP Act, perceived cost anxiety may also prevent individuals from seeking immunizations, ultimately showcasing the necessity of easily accessible, low-barrier, community-engaged programs prioritizing vaccine accessibility. (7,13)

Taking action on vaccine equity moving forward

As infectious diseases professionals, we can take action to promote vaccine equity across minoritized communities. First, we can continue to educate the community about the availability of up-to-date COVID-19 vaccinations and inform them about the payment coverage available for the immunization. Additionally, we can collaborate with community partners, including local and state health departments, to provide vaccinations in easily accessible formats. Finally, we can continue to advocate for funding allocated to initiatives that address accessibility barriers to vaccinations. Many lessons were learned during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic — we must continue to pay the actions forward.

Photo, top left: Dr. Jacinda Abdul-Mutakabbir (seated) immunizes a San Bernadino County resident at a community vaccination clinic held at 16th Street Seventh Day Adventist Church in San Bernadino, California, in April 2021 as Gov. Gavin Newsom (standing, center), local elected officials and Black church leaders watch.

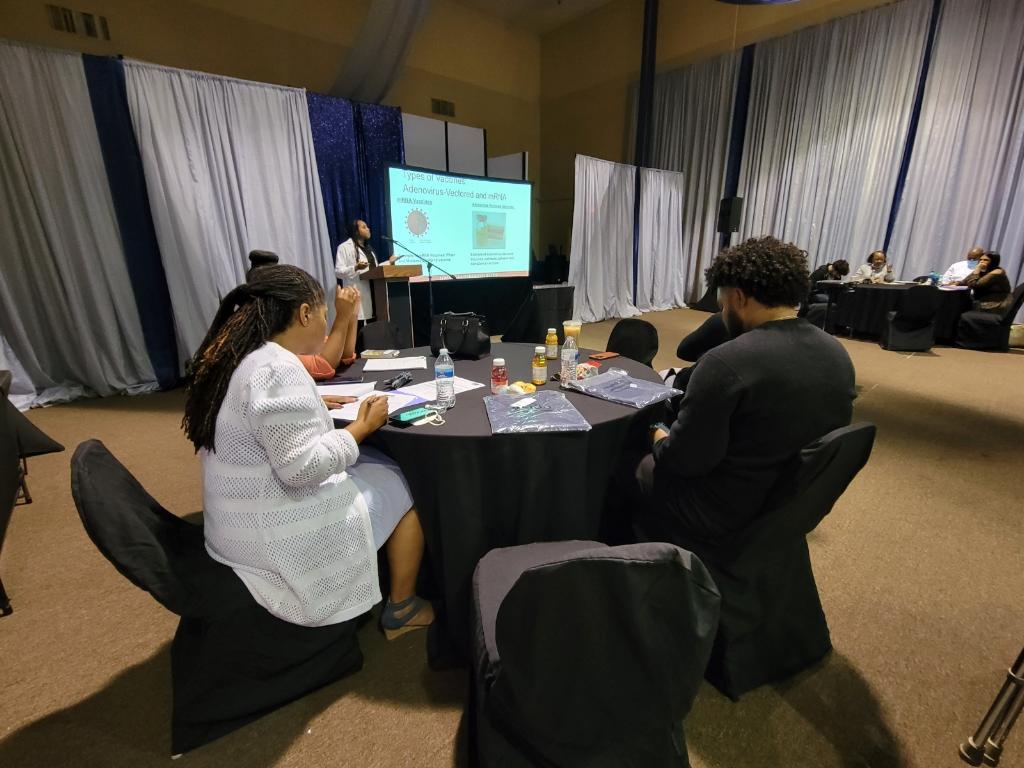

Photo, middle right: Dr. Abdul-Mutakabbir (at podium) speaks to the congregation of Immanuel Praise Fellowship Church in Rancho Cucamonga, California, about respiratory viruses and vaccines in November 2022.

References

- Khazanchi R, Evans CT, Marcelin JR. Racism, Not Race, Drives Inequity Across the COVID-19 Continuum. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2019933-e2019933. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19933

- Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, Bernice F, et al. Addressing and Inspiring Vaccine Confidence in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(9):ofab417. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab417

- Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Casey S, Jews V, et al. A three-tiered approach to address barriers to COVID-19 vaccine delivery in the Black community. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00099-1

- Egede LE, Walker RJ. Structural Racism, Social Risk Factors, and Covid-19 — A Dangerous Convergence for Black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(12):e77. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023616

- Warren RC, Forrow L, Hodge DA, Sr., Truog RD. Trustworthiness before Trust - Covid-19 Vaccine Trials and the Black Community. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):e121. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2030033

- Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Granillo C, Peteet B, et al. Rapid Implementation of a Community–Academic Partnership Model to Promote COVID-19 Vaccine Equity within Racially and Ethnically Minoritized Communities. Vaccines. 2022;10(8):1364.

- Fact Sheet: HHS Announces Intent to Amend the Declaration Under the PREP Act for Medical Countermeasures Against COVID-19. Availbale from: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/04/14/factsheet-hhs-announces-amend-declaration-prep-act-medical-countermeasures-against-covid19.html. Accessed May 2024.

- Community-Based Outreach to Build COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/coronavirus/community-based-outreach. Accessed May 2024.

- Health Disparities: Provisional Death Counts for COVID-19. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.html. Accessed May 2024.

- Vaccination Trends — Adults. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/data-research/dashboard/vaccination-trends-adults.html. Accessed May 2024.

- COVID-19 Vaccination Data. Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-Vaccine-Data.aspx#Age. Accessed May 2024.