How a summer exploring mpox vaccination disparities piqued my interest in ID

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email After my first year as a medical student at San Juan Bautista School of Medicine in Puerto Rico, this past summer I was a Center for AIDS Research Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, where I immersed myself in HIV and infectious diseases research. Although I initially had no particular interest in ID, this experience broadened my perspective. I had the opportunity to shadow ID physicians, gaining insights into clinical practices and hospital rounds. Witnessing a variety of infectious diseases firsthand, I was captivated by their uniqueness and the distinct thought processes required for each diagnosis. This experience sparked my interest in ID, a field where every case is like solving a new mystery.

After my first year as a medical student at San Juan Bautista School of Medicine in Puerto Rico, this past summer I was a Center for AIDS Research Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, where I immersed myself in HIV and infectious diseases research. Although I initially had no particular interest in ID, this experience broadened my perspective. I had the opportunity to shadow ID physicians, gaining insights into clinical practices and hospital rounds. Witnessing a variety of infectious diseases firsthand, I was captivated by their uniqueness and the distinct thought processes required for each diagnosis. This experience sparked my interest in ID, a field where every case is like solving a new mystery.

Additionally, I contributed to a survey study on mpox vaccination among individuals with HIV at a Penn HIV clinic, which led me to delve deeper into the mpox vaccination rollout. As an emerging underrepresented minority in medicine trainee who seeks to address disparities in health that still exist in our health care system, I want to share my perspective on this experience, the study’s results and the implications — for public health and for my own potential career path

What the study found

In a survey of patients with HIV who had already received the COVID-19 vaccine, we found that mpox vaccine acceptance was high; however, actual vaccination rates were low. A total of 59 out of 80 participants (74%) stated that they intended to get vaccinated, while four participants (5%) declined, and 17 participants (21%) remained unsure or did not provide a response. Among those who intended to receive the mpox vaccine, only 31% received it. Notable disparities in vaccination rates were observed by race: Of those who received the mpox vaccine, 48% identified as Black, but Black patients comprise 74% of the clinic population.

The mpox vaccine rollout created challenges for providers as there was a limited supply of vaccines; this required prioritizing high-risk populations. (1) The generation of highly specific jurisdictions for vaccine uptake at the initial outbreak of the virus was one of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, where precious vaccine supply was not adequately prioritized for marginalized groups. While this approach represented an important first step, there was a mismatch between the intention to get vaccinated and actual receipt of vaccine, which highlights the need to develop or strengthen academic and community partnerships to achieve vaccine equity.

Based on data as of July 11, 2023, obtained from the city of Philadelphia, a noticeable trend emerges regarding the demographic disparities in mpox cases and vaccinated individuals. Concerningly, around 60% of all mpox cases affected Black or African American individuals, while White individuals made up only 20% of the cases, and Latinos accounted for 17% of the cases. Despite this disproportionate burden among the Black or African American community, the vaccination statistics show a different picture. More than half of those vaccinated (53%) were White, indicating a higher proportion of White individuals receiving vaccinations compared to their representation in mpox cases. (2) Additionally, 26% of the vaccinated individuals were Black or African American, followed by 12% who were Hispanic or Latino, and 6% who were Asian. (2) These statistics highlight the urgent need for targeted efforts to address the disparities in both mpox cases and vaccination rates, ensuring equitable access to vaccinations for all demographics and fostering a healthier, more inclusive Philadelphia.

Strategies to address the discrepancy

After conducting additional research and consulting health care professionals, I suggest the following strategies to help address the gap between high vaccine acceptance and low mpox vaccination rates:

- Strengthening Health Care Infrastructure: Efforts should be directed towards expanding health care infrastructure, particularly in underserved areas with high-risk populations, to improve access to vaccination services. Mobile clinics, outreach programs and community-based initiatives can help overcome barriers related to accessibility and affordability.

- Enhanced Public Education: Investing in targeted public education campaigns is essential to dispel misinformation, address vaccine hesitancy and reinforce the importance and safety of the mpox vaccine. These campaigns should utilize clear, evidence-based messaging, involving trusted health care professionals, to counteract false information effectively.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Effective collaboration between public health authorities, health care providers and community leaders is crucial. By working together, they can pool resources, share expertise and develop tailored vaccination strategies that address the specific needs and concerns of different communities. The high-risk population that was surveyed for this study may help in serving as vaccine ambassadors in their community and help overcome hesitancy.

- Improved Vaccine Supply Chain: Efforts must be made to ensure an adequate and stable supply of mpox vaccines. This involves strengthening the vaccine supply chain, optimizing production and implementing mechanisms to address any potential shortages promptly.

The time to act is now

While I was encouraged by the data showing that mpox vaccine acceptance was high in this sample, it was disheartening to see the discrepancy between acceptance and actual vaccination rates. Proactive measures are needed to address the underlying factors contributing to this gap. By enhancing accessibility, combating vaccine hesitancy, improving vaccine supply and promoting education, we can strive to achieve higher vaccination rates, protect vulnerable populations and effectively mitigate the impact of mpox outbreaks. The time to act is now, as collective efforts in vaccination are crucial for public health and the well-being of our communities, before another outbreak starts.

This summer experience was truly transformative for me because for this first time in my life, I could see myself as a future ID physician, taking care of patients and thinking critically about public health issues. My involvement in the mpox vaccination study reinforced my interest in research and sparked a newfound enthusiasm for ID as a potential career path. Furthermore, being accepted into this program highlights the value of programs focused on underrepresented minorities in medicine in empowering minority students like me to pursue their goals and make meaningful contributions in health care and research.

References

- Knight, J., Tan, D. H. S., & Mishra, S. (2022). Maximizing the impact of limited vaccine supply under different early epidemic conditions: A 2-city modelling analysis of monkeypox virus transmission among men who have sex with men. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 194(46), E1560–E1567.

- Board of Health, Department of Public Health. (2023, May 25). Demographic characteristics of Philadelphians vaccinated against mpox. Philadelphia; City of Philadelphia: Programs and initiatives.

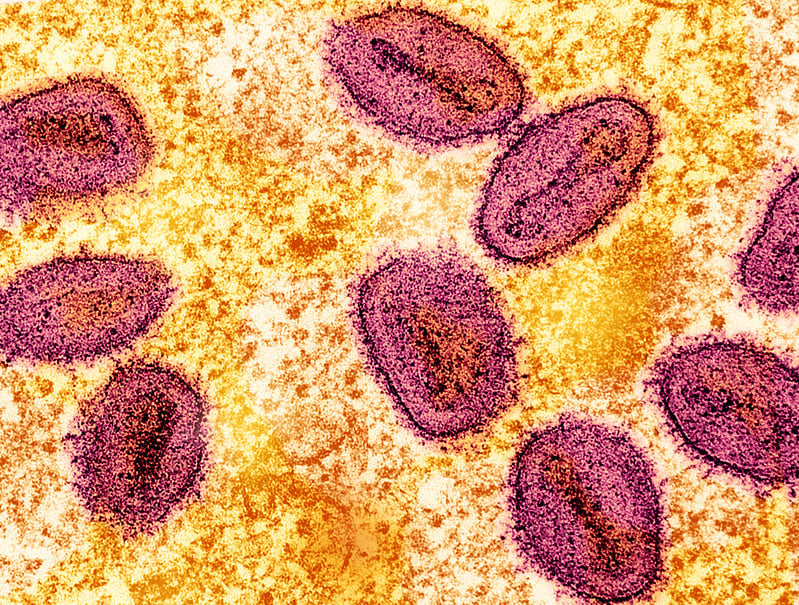

Photo: Colorized transmission electron micrograph of mpox virus particles (pink) found within an infected cell (yellow), cultured in the laboratory. Image captured at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID.