Sandra R. Arnold, Andrej Spec, John W. Baddley, Robert J. Lentz, Peter Pappas, Joshua Wolf, Kayla R. Stover, Nathan P. Wiederhold, Monica I. Ardura, Nevert Badreldin, Nathan C. Bahr, Karen Bloch, Carol Kauffman, Rachel A. Miller, Satish Mocherla, Michael Saccente, Ilan Schwartz, Jennifer Loveless

An overview manuscript can be found here.

Update History

This is Part 1 of an update to the 2007 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Histoplasmosis.

Background

As the first part of an update to the clinical practice guideline on the management of histoplasmosis in adults, children, and pregnant people, developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, we present 4 updated recommendations. These recommendations span treatment of asymptomatic Histoplasma pulmonary nodules (histoplasmomas) and mild and moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. The panel’s recommendations are based upon evidence derived from systematic literature reviews and adhere to a standardized methodology for rating the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendation according to the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach.

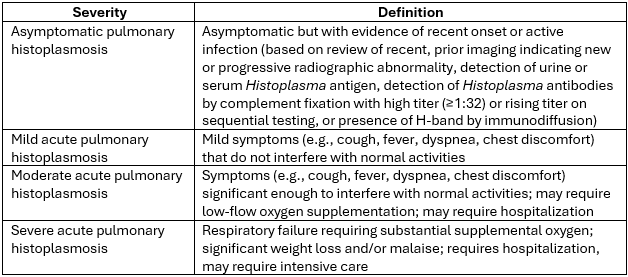

Histoplasmosis is caused by infection with the thermally dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasmosis occurs through inhalation of H. capsulatum which has a worldwide distribution but is hyperendemic in specific areas such as the midwestern United States. Histoplasmosis syndromes include pulmonary and disseminated disease, the spectrum of which varies from asymptomatic to severe disease depending on inoculum and cell-mediated immune function. Asymptomatic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and mild, moderate, and severe acute pulmonary histoplasmosis are defined in Table 1.

Table 1. Severity of Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

These definitions are offered as guidance but are not intended to be prescriptive. Clinical assessment should drive care decisions.

Methods

The panel included clinicians with expertise in infectious diseases, pediatric infectious diseases, pulmonology, maternal-fetal medicine, and pharmacology. Selected reviewers included clinicians with expertise in infectious diseases and pediatric infectious diseases. The following organizations reviewed and provided feedback on the associated manuscripts: Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists.

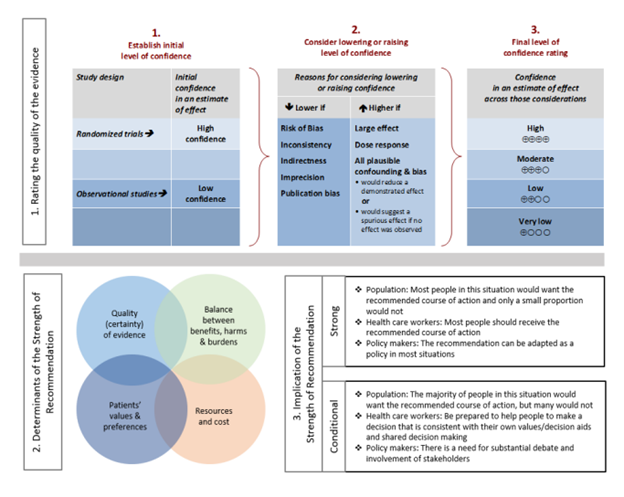

For each question, a systematic review was performed to identify relevant studies, and the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach was followed for assessing the certainty of evidence and strength of recommendation (Figure 1).

Details of the systematic review and guideline development processes are available in the supplemental materials for each included manuscript.

Figure 1. Approach and implications to rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations using GRADE methodology (unrestricted use of figure granted by the U.S. GRADE Network)

Recommendation: Treatment of Asymptomatic Histoplasma Pulmonary Nodules (Histoplasmomas)

This recommendation is endorsed by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS), the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharamacists (SIDP), and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC)

Section last reviewed on 03/12/2025

Last literature search conducted January 2024

[View supplemental material here]

In patients with asymptomatic, previously untreated Histoplasma pulmonary nodules (histoplasmomas), for which patients should antifungal treatment be initiated?

Recommendation

In adults and children with asymptomatic non-calcified pulmonary nodules related to histoplasmosis with no evidence of other active sites, or asymptomatic patients with known untreated prior infection, the panel suggests against routinely providing treatment for histoplasmosis to prevent reactivation (conditional* recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks

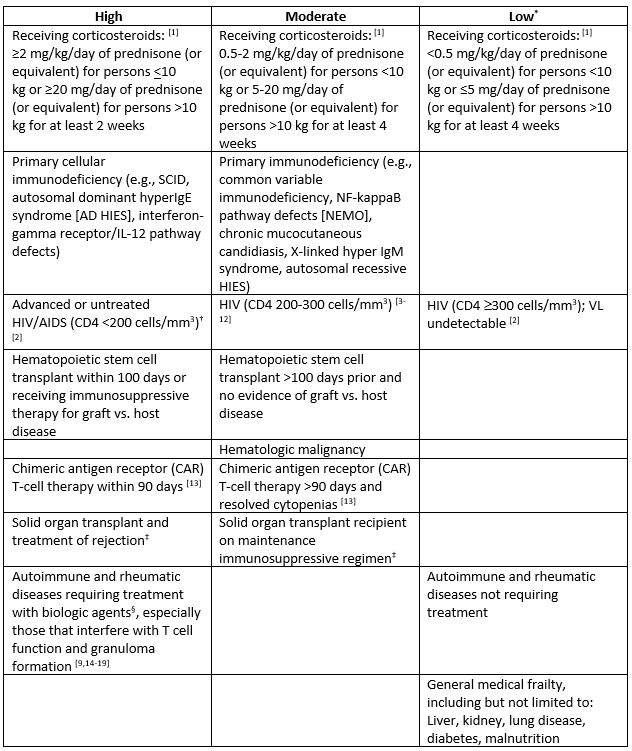

- In patients with elevated risk for disseminated/severe histoplasmosis (especially those with immunocompromising conditions that confer high and moderate risk according to Table 1), closely monitor for clinical/radiological change or consider treatment.

- Patients with only calcified pulmonary nodules should not be treated.

- Treatment of pregnant individuals should only be considered after carefully weighing the potential benefits vs. harms of treatment, ideally in consultation with a maternal fetal medicine specialist and an infectious diseases specialist, as these cases are rare, complex, and highly variable. If treatment is necessary, azoles should be avoided in the first trimester when possible and liposomal amphotericin B used instead.

*Conditional recommendations are made when the suggested course of action would apply to the majority of people with many exceptions, and shared decision-making is important.

Table 1. Categories of Immunocompromise and Risk for Disseminated/Severe Histoplasmosis

Categories of immunocompromise represent a continuum rather than distinct categories. Conditions are categorized here as a guide; given limited evidence, this table is not exhaustive or exact.

*The following conditions confer no known increased risk: sickle cell disease and other asplenia syndromes; antibody, complement, or neutrophil deficiencies.

†Severe immunocompromise in children ≤5 years of age is defined as CD4+T lymphocyte [CD4+] percentage <15%, and in individuals ≥6 years, CD4+percentage <15% and CD4+ >200 lymphocytes/mm3 [1].

‡Carefully consider drug-drug interactions (e.g., tacrolimus for Graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] prophylaxis).

§There are a variety of biologic agents with varying levels of immunosuppression. Serious infections have happened in patients receiving biologic response modifiers, including tuberculosis and disseminated infections caused by viruses, fungi, or bacteria. Frequently reported biologics associated with disseminated/severe histoplasmosis include: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNF-alpha inhibitors, e.g., infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab); IL12/IL23 blockade (ustekinumab, risankizumab, guselkumab).

Results

Twenty-one studies (including case series and case reports) that addressed efficacy of antifungal therapy of asymptomatic pulmonary nodules in adults and children were identified [3-12,15-25]. Included studies reported on the outcomes of progression to disseminated disease or significant pulmonary disease, reactivation of latent disease, and possible predisposing factors. We did not find any studies addressing this question in pregnant people.

Rationale for Recommendations

Most patients who have asymptomatic pulmonary nodules (histoplasmomas) do not require therapy. In many cases, histoplasmomas represent past or dormant infection. However, there is the possibility of reactivation of infection, worsening pulmonary disease or disseminated disease. Based on published reports, it is unclear which underlying host conditions or other factors may lead to reactivation (Table 1). This literature review supports that many reported patients with likely reactivation were immunocompromised. Moreover, the time to reactivation varies greatly and may occur decades after initial infection. In some patients, the risk of reactivation may be higher and treatment to prevent reactivation should be discussed thoroughly with the patient or caregivers. Although itraconazole is typically safe, it is important to consider potential adverse effects, drug-drug interactions or other associated issues (costs) related to prolonged therapy. The panel agrees that the overall balance of benefits and harms favors avoiding routine treatment of asymptomatic histoplasmomas.

References

- Kroger A, Bahta L, Long S, Sanchez P. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization: Altered Immunocompetence. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/immunocompetence.html. Accessed 06/16/2024.

- Panel on guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2024. Accessed 12/12/2024.

- Antinori S, Magni C, Nebuloni M, et al. Histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2006, 85(1):22–36.

- Anderson AM, Mehta AK, Wang YF, et al. HIV-associated histoplasmosis in a nonendemic area of the United States during the HAART era: role of migration from endemic areas and lack of antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 2010, 9(5):296–300.

- Ashbee HR, Evans EGV, Viviani MA, et al. Histoplasmosis in Europe: report on an epidemiological survey from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology Working Group. Med Mycol 2008, 46(1): 57–65.

- Bourgeois N, Douard-Enault C, Reynes J, et al. Seven imported histoplasmosis cases due to Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum: From few weeks to more than three decades asymptomatic period. J Mycol Med 2011, 21(1):19–23.

- Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martinez L, Castelli MV, et al. Histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis in a non-endemic area: a review of cases and diagnosis. J Travel Med 2011, 18(1):26–33.

- Choi J, Nikoomanesh K, Uppal J, Wang, S. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis with concomitant disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in a patient with AIDS from a nonendemic region (California). BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19(1):46.

- Gandhi V, Ulyanovskiy P, Epelbaum O. Update on the spectrum of histoplasmosis among Hispanic patients presenting to a New York City municipal hospital: a contemporary case series. Respir Med Case Rep 2015, 16:60–64.

- Peigne V, Dromer F, Elie C, et al. Imported acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related histoplasmosis in metropolitan France: a comparison of pre-highly active anti-retroviral therapy and highly active anti-retroviral therapy eras. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011, 85(5):934–941.

- Martin-Iguacel R, Kurtzhals J, Jouvion G, Nielsen SD, Llibre JM. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in the HIV population in Europe in the HAART era: case report and literature review. Infection 2014, 42(4):611–620.

- Norman FF, Martin-Davila P, Fortun J, et al. Imported histoplasmosis: two distinct profiles in travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med 2009, 16(4):258–262.

- Shahid Z, Jain T, Dioverti V, et al. Best practice considerations by the American Society of Transplant and Cellular Therapy: infection prevention and management after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for hematological malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther 2024, 30(1):955–969.

- Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, Helper D, Kleiman MB, Wheat LJ. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2010, 50(1):85–92.

- Jain VV, Evans T, Peterson MW. Reactivation histoplasmosis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha in a patient from a nonendemic area. Respir Med 2006, 100(7):1291–1293.

- Lucey O, Carroll I, Bjorn T, Millar M. Reactivation of latent Histoplasma and disseminated cytomegalovirus in a returning traveller with ulcerative colitis. JMM Case Rep 2018, 5(12):e005170.

- Prakash K, Richman D. A case report of disseminated histoplasmosis and concurrent cryptococcal meningitis in a patient treated with ruxolitinib. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19(1):287.

- Sani S, Bilal J, Varma E, et al. Not your typical Arizona granuloma: a case report of disseminated histoplasmosis. Am J Med 2018, 131(9):e375–e376.

- Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, et al. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Infect Dis 2004, 38(9):1261–1265.

- Alamri M, Albarrag AM, Khogeer H, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a heart transplant recipient from Saudi Arabia: a case report. J Infect Public Health 2021, 14(8):1013–1017.

- Carmans L, Van Craenenbroeck A, Lagrou K, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a kidney liver transplant patient from a non-endemic area: a diagnostic challenge. IDCases 2020, 22:e00971.

- Demkowicz, R, Procop GW. Clinical significance and histologic characterization of Histoplasma granulomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2021, 155(4):581–587.

- Garcia-Marron M, Garcia-Garcia JM, Pajin-Collada M, et al. Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis diagnosed in a nonimmunosuppresed patient 10 years after returning from an endemic area. Arch Bronconeumol 2008, 44(10):567–570.

- Hess J, Fondell A, Fustino N, et al. Presentation and treatment of histoplasmosis in pediatric oncology patients: Case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017, 39(2):137–140.

- Chang B, Saleh T, Wales C, et al. Case report: disseminated histoplasmosis in a renal transplant recipient from a non-endemic region. Front Pediatr 2022; 10:985475.

Recommendation: Treatment of Mild or Moderate Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

These recommendations are endorsed by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS), the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP), and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC)

Section last reviewed on 03/12/2025

Last literature search conducted January 2024

[View supplemental material here]

In patients presenting with mild or moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, should antifungal treatment be given for resolution of symptoms?

Recommendation

In immunocompetent adults and children presenting with mild acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, the panel suggests against routinely providing antifungal treatment (conditional* recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remark

- Treatment may be considered in immunocompetent patients with mild acute pulmonary histoplasmosis and prolonged duration of illness, progression of pulmonary infiltrates, or enlarging hilar or mediastinal adenopathy. In a large outbreak study, >75% of persons affected were ill for 1 week or less, and all recovered completely within 2 months without treatment [1].

*Conditional recommendations are made when the suggested course of action would apply to the majority of people with many exceptions, and shared decision-making is important.

Recommendation

In immunocompetent adults and children presenting with moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, the panel suggests either antifungal treatment or no antifungal treatment, considering the severity and duration of signs/symptoms, as well as potential harms of antifungal treatment (conditional* recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks

- Moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis includes a heterogeneous group of patients. Prolonged duration of illness, worsening symptoms, progression of pulmonary infiltrates, enlarging hilar or mediastinal adenopathy, and more severe signs or symptoms favor treatment.

- Consider drug-drug interactions and other potential harms vs. benefits of antifungal treatment when deciding whether to treat. Potential financial burden should be discussed with the patient as well.

- The goals of treatment are to decrease the duration of illness and mitigate risk of dissemination, though treatment effectiveness in this patient population is unknown.

- When treatment is indicated, itraconazole is preferred [2].

- Initial dosing for original itraconazole capsules or oral solution: (adults: 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days and then 200 mg twice daily for 6-12 weeks; children: 5 mg/kg/dose [up to a max of 200 mg/dose] three times daily for 3 days and then 5 mg/kg/dose twice daily [not to exceed 400 mg daily] for 6-12 weeks). Super-Bioavailable (SUBA) itraconazole (only available as capsules and currently approved for use in adults): 130 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, then 130 mg twice daily for 6-12 weeks. In consultation with a pharmacist, similar dosing for SUBA itraconazole based on the child’s weight may be considered in children old enough to swallow capsules (as off-label use). For additional information on the various itraconazole formulations, see Implementation Considerations section.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) should be performed for patients receiving itraconazole [3-6]. In recent studies, ~20% of patients required dose adjustments due to sub- or super-therapeutic levels of itraconazole, and ~28% of patients experienced side effects [7,8]. A goal trough concentration of itraconazole component >1 mg/L and <3-4 mg/L (as measured by chromatographic assay) is associated with efficacy and a lower risk of toxicity [3-7,9-11]. Due to the long half-life of itraconazole, non-trough/random levels of itraconazole can also be used to monitor serum concentrations. Hydroxy-itraconazole is an active metabolite; however, a cutoff for combined hydroxy-itraconazole and itraconazole levels has not been established [10,12,13]. Patients with a combined hydroxy-itraconazole and itraconazole level >2 mg/L may respond similarly to patients with itraconazole levels >1 mg/L [14].

- Treatment of pregnant individuals should only be considered after carefully weighing the potential benefits vs. harms of treatment, ideally in consultation with a maternal fetal medicine specialist and an infectious diseases specialist, as these cases are rare, complex, and highly variable. If treatment is necessary, azoles should be avoided in the first trimester when possible and liposomal amphotericin B used instead.

*Conditional recommendations are made when the suggested course of action would apply to the majority of people with many exceptions, and shared decision-making is important.

Recommendation

In immunocompromised adults and children presenting with mild or moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis who are at moderate to high risk of progression to disseminated disease, the panel suggests antifungal treatment (conditional* recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks

- Patients with asymptomatic or mild acute pulmonary histoplasmosis and a lesser degree of immunocompromise (see Table 1) may not warrant treatment.

- When treatment is indicated, itraconazole is preferred [2].

- Initial dosing for original itraconazole capsules or oral solution: (adults: 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days and then 200 mg twice daily for 6-12 weeks; children: 5 mg/kg/dose [up to a max of 200 mg/dose] three times daily for 3 days and then 5 mg/kg/dose twice daily [not to exceed 400 mg daily] for 6-12 weeks). SUBA itraconazole (only available as capsules and currently approved for use in adults): 130 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, then 130 mg twice daily for 6-12 weeks (similar dosing may be considered in children old enough to swallow capsules).

- Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) should be performed for patients receiving itraconazole [3-6]. In recent studies, ~20% of patients required dose adjustments due to sub- or super-therapeutic levels of itraconazole, and ~28% of patients experienced side effects [7,8]. A goal trough concentration of itraconazole component >1 mg/L and <3-4 mg/L (as measured by chromatographic assay) is associated with efficacy and a lower risk of toxicity [3-7,9-11]. Due to the long half-life of itraconazole, non-trough/random levels of itraconazole can also be used to monitor serum concentrations. Hydroxy-itraconazole is an active metabolite; however, a cutoff for combined hydroxy-itraconazole and itraconazole levels has not been established [10,12,13]. Patients with a combined hydroxy-itraconazole and itraconazole level >2 mg/L may respond similarly to patients with itraconazole levels >1 mg/L [14].

- Treatment of pregnant individuals should only be considered after carefully weighing the potential benefits vs. harms of treatment, ideally in consultation with a maternal fetal medicine specialist and an infectious diseases specialist, as these cases are rare, complex, and highly variable. If treatment is necessary, azoles should be avoided in the first trimester when possible and liposomal amphotericin B used instead.

*Conditional recommendations are made when the suggested course of action would apply to the majority of people with many exceptions, and shared decision-making is important.

Table 1. Categories of Immunocompromise and Risk for Disseminated/Severe Histoplasmosis

Categories of immunocompromise represent a continuum rather than distinct categories. Conditions are categorized here as a guide; given limited evidence, this table is not exhaustive or exact.

*The following conditions confer no known increased risk: sickle cell disease and other asplenia syndromes; antibody, complement, or neutrophil deficiencies.

†Severe immunocompromise in children ≤5 years of age is defined as CD4+T lymphocyte [CD4+] percentage <15%, and in individuals ≥6 years, CD4+percentage <15% and CD4+ >200 lymphocytes/mm3 [15].

‡Carefully consider drug-drug interactions (e.g., tacrolimus for Graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] prophylaxis).

§There are a variety of biologic agents with varying levels of immunosuppression. Serious infections have happened in patients receiving biologic response modifiers, including tuberculosis and disseminated infections caused by viruses, fungi, or bacteria. Frequently reported biologics associated with disseminated/severe histoplasmosis include: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNF-alpha inhibitors, e.g., infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab); IL12/IL23 blockade (ustekinumab, risankizumab, guselkumab).

Results

Limited evidence was identified for the outcomes of mortality (9 studies [1,34-41]), symptom resolution/radiographic regression (9 studies [1,34-37,39-42]), and toxicity (1 study [35]).

Rationale for Recommendations

The studies demonstrate that most cases of mild-to-moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis will resolve without treatment. Data on the prevalence of Histoplasma capsulatum exposure, rate at which significant illness develops, and prognosis of non-severe acute pulmonary disease largely derive from population-level histoplasmin sensitivity studies and large outbreak reports, most dating from the 1950s-80s. These indicate that exposure to H. capsulatum is widespread in endemic areas, with over half of children by age 8 [43] and more than 80% of long-term residing adults [44] demonstrating an immunologic response to Histoplasma antigen. Most infections are subclinical with an estimated fewer than 5% of exposed individuals developing even mild symptoms [42]. In a large urban outbreak study involving an estimated 120,000 individuals, only 435 cases (0.36%) were identified in a hospital setting (therefore likely to meet current criteria for moderate or severe disease) [45]. At most, 4 of 285 individuals with acute respiratory disease required treatment, with all others recovering without treatment. In another large outbreak involving 383 junior high school students and some adult staff, only one patient required hospitalization and all recovered without treatment, most within 2 weeks of symptom onset [1].

Treatment decisions also require an assessment of the potential harms of treatment. Itraconazole is associated with several common undesirable effects, including nausea and vomiting, rash, and peripheral edema. More serious complications, including hepatotoxicity and heart failure, are rare but have been reported. Itraconazole is a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor with many significant drug-drug interactions and is known to have highly variable oral absorption requiring monitoring of drug levels. Its use is contraindicated in the first trimester of pregnancy, necessitating involvement of maternal fetal medicine and infectious diseases specialists and use of alternative agents such as amphotericin B with potentially greater undesirable effects. Treatment duration of 6-12 weeks imposes a large pill burden, most notably for children. Overall, the panel assesses the burden of undesirable effects to be typically small in children, moderate in adults, and large in pregnant people. Treatment courses may also be associated with significant cost with variable insurance coverage.

In the context of most immunocompetent patients with mild to moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis recovering without specific treatment while several potential harms of treatment are apparent, the panel agrees that the overall balance of benefits versus harms favors not treating with an antifungal medication in most cases. Greater consideration to treatment may be appropriate in cases with more prolonged symptom duration (e.g., >1 month), progressive symptoms or radiographic abnormalities, or more severe initial symptoms. Treatment in these scenarios would be intended to shorten duration of symptoms, prevent progression to more severe disease, and/or prevent late sequalae of pulmonary histoplasmosis such as mediastinal granuloma or fibrosing mediastinitis. However, there are no data demonstrating treatment is associated with any of these potentially improved clinical outcomes.

Progression to severe acute pulmonary histoplasmosis or disseminated disease appears rare in immunocompetent patients in large outbreak studies. However, immunocompromise has been identified as a clear risk factor for more severe disease in these and other reports [46]. For this reason, the panel agrees that the overall balance of benefits to harms favors antifungal treatment in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis and an underlying immunocompromise that places them at significant risk for disease progression.

References

- Brodsky AL, Gregg MB, Loewenstein MS, Kaufman L, Mallison GF. Outbreak of histoplasmosis associated with the 1970 Earth Day activities. Am J Med 1973;54(3):333–342.

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006, 45:807–825.

- Ashbee HR, Barnes RA, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Gorton R, Hope WW. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antifungal agents: guidelines from the British Society for Medical Mycology. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014, 69(5):1162–1176.

- Chau MM, Daveson K, Alffenaar J-WC, et al. Consensus guidelines for optimizing antifungal drug delivery and monitoring to avoid toxicity and improve outcomes in patients with haematological malignancy and haemopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2021. Intern Med J 2021, 51 Suppl 7:37-66.

- Laverdiere M, Bow EJ, Rotstein C, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring for triazoles: a needs assessment review and recommendations from a Canadian perspective. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2014, 25(6):327–343.

- McCreary EK, Davis MR, Narayanan N, et al. Utility of triazole antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists: endorsed by the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Pharmacotherapy 2023, 43(10):1043–1050.

- Osborn MR, Zuniga-Moya JC, Mazi PB, Rauseo AM, Spec A. Side effects associated with itraconazole therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024; dkae437.

- Spec A, Thompson GR, Miceli MH, et al. MSG-15: super-bioavailability itraconazole versus conventional itraconazole in the treatment of endemic mycoses—a multicenter, open-label, randomized comparative trial. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024, 11(3), ofae010.

- Andes D, Pascual A, Marchetti O. Antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: established and emerging indications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53(1):24–34.

- Cartledge JD, Midgely J, Gazzard BG. Itraconazole solution: higher serum drug concentrations and better clinical response rates than the capsule formulation in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with candidosis. J Clin Pathol 1997, 50(6):477–480.

- Lestner JM, Roberts SA, Moore CB, Howard SJ, Denning DW, Hope WW. Toxicodynamics of itraconazole: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 49(6):928–930.

- Firkus D, Abu Saleh OM, Enzler MJ, et al. Does metabolite matter? Defining target itraconazole and hydoxy-itraconazole serum concentrations for blastomycosis. Mycoses 2023, 66(5):412–419.

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Singh A, et al. Predicting a therapeutic cut-off serum level of itraconazole in recalcitrant tinea corporis and cruris– a prospective trial. Mycoses 2021, 64(12):1480–1488.

- Wiederhold NP, Schwartz IS, Patterson TF, Thompson III, GR. Variability of hydroxy-itraconazole in relation to itraconazole bloodstream concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65(4):e02353–20.

- Kroger A, Bahta L, Long S, Sanchez P. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization: Altered Immunocompetence. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/immunocompetence.html. Accessed 06/16/2024.

- Panel on guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2024. Accessed 12/12/2024.

- Ashbee HR, Evans EGV, Viviani MA, et al. Histoplasmosis in Europe: report on an epidemiological survey from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology Working Group. Med Mycol 2008, 46(1): 57–65.

- Antinori S, Magni C, Nebuloni M, et al. Histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2006, 85(1):22–36.

- Anderson AM, Mehta AK, Wang YF, et al. HIV-associated histoplasmosis in a nonendemic area of the United States during the HAART era: role of migration from endemic areas and lack of antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 2010, 9(5):296–300.

- Bourgeois N, Douard-Enault C, Reynes J, et al. Seven imported histoplasmosis cases due to Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum: From few weeks to more than three decades asymptomatic period. J Mycol Med 2011, 21(1):19–23.

- Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martinez L, Castelli MV, et al. Histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis in a non-endemic area: a review of cases and diagnosis. J Travel Med 2011, 18(1):26–33.

- Choi J, Nikoomanesh K, Uppal J, Wang, S. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis with concomitant disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in a patient with AIDS from a nonendemic region (California). BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19(1):46.

- Gandhi V, Ulyanovskiy P, Epelbaum O. Update on the spectrum of histoplasmosis among Hispanic patients presenting to a New York City municipal hospital: a contemporary case series. Respir Med Case Rep 2015, 16:60–64.

- Peigne V, Dromer F, Elie C, et al. Imported acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related histoplasmosis in metropolitan France: a comparison of pre-highly active anti-retroviral therapy and highly active anti-retroviral therapy eras. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011, 85(5):934–941.

- Martin-Iguacel R, Kurtzhals J, Jouvion G, Nielsen SD, Llibre JM. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in the HIV population in Europe in the HAART era: case report and literature review. Infection 2014, 42(4):611–620.

- Norman FF, Martin-Davila P, Fortun J, et al. Imported histoplasmosis: two distinct profiles in travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med 2009, 16(4):258–262.

- Shahid Z, Jain T, Dioverti V, et al. Best practice considerations by the American Society of Transplant and Cellular Therapy: infection prevention and management after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for hematological malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther 2024, 30(1):955–969.

- Hage CA, Bowyer S, Tarvin SE, Helper D, Kleiman MB, Wheat LJ. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor blocker therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2010, 50(1):85–92.

- Jain VV, Evans T, Peterson MW. Reactivation histoplasmosis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha in a patient from a nonendemic area. Respir Med 2006, 100(7):1291–1293.

- Lucey O, Carroll I, Bjorn T, Millar M. Reactivation of latent Histoplasma and disseminated cytomegalovirus in a returning traveller with ulcerative colitis. JMM Case Rep 2018, 5(12):e005170.

- Prakash K, Richman D. A case report of disseminated histoplasmosis and concurrent cryptococcal meningitis in a patient treated with ruxolitinib. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19(1):287.

- Sani S, Bilal J, Varma E, et al. Not your typical Arizona granuloma: a case report of disseminated histoplasmosis. Am J Med 2018, 131(9):e375–e376.

- Wallis RS, Broder MS, Wong JY, et al. Granulomatous infectious diseases associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Clin Infect Dis 2004, 38(9):1261–1265.

- Chamany S, Mirza SA, Fleming JW, et al. A large histoplasmosis outbreak among high school students in Indiana, 2001. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004, 23(10):909–914.

- Dismukes WE, Bradsher RW, Cloud GC, et al. Itraconazole therapy for blastomycosis and histoplasmosis. NIAID Mycoses Study Group. Am J Med 1992, 93(5):489–497.

- Hess J, Fondell A, Fustino N, et al. Presentation and treatment of histoplasmosis in pediatric oncology patients: Case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017, 39(2):137–140.

- Muhi S, Crowe A, Daffy J. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis outbreak in a documentary film crew travelling from Guatemala to Australia. Trop Med Infect Dis 2019, 4(1):25.

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, & Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998-2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011, 11:145.

- Oulette CP, Stanek JR, Leber A, Ardura MI. Pediatric histoplasmosis in an area of endemicity: a contemporary analysis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019, 8(5):400–407.

- Staffolani S, Riccardi N, Farina C, et al. Acute histoplasmosis in travelers: a retrospective study in an Italian referral center for tropical disease. Pathog Glob Health 2020, 114(1):40–45.

- Agossou M, Turmel J-M, Aline-Fardin A, Venissac N, & Desbois-Nogard N. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in immunocompetent subjects from Martinique, Guadeloupe and French Guiana: a case series. BMC Pulm Med 2023, 23(1):95.

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989, 8(5):480–490.

- Christie A, Peterson JC. Histoplasmin sensitivity. J Pediatr 1946;29(4):417–432.

- Edwards LB, Acquaviva FA, Livesay VT. Further observations on histoplasmin sensitivity in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1973, 98(5):315–325.

- Wheat LJ, Slama TG, Eitzen HE, Kohler RB, French ML, Biesecker JL. A large urban outbreak of histoplasmosis: clinical features. Ann Intern Med 1981, 94(3):331–337.

- Sathapatayavongs B, Batteiger BE, Wheat J, Slama TG, Wass JL. Clinical and laboratory features of disseminated histoplasmosis during two large urban outbreaks. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62(5):263–270.