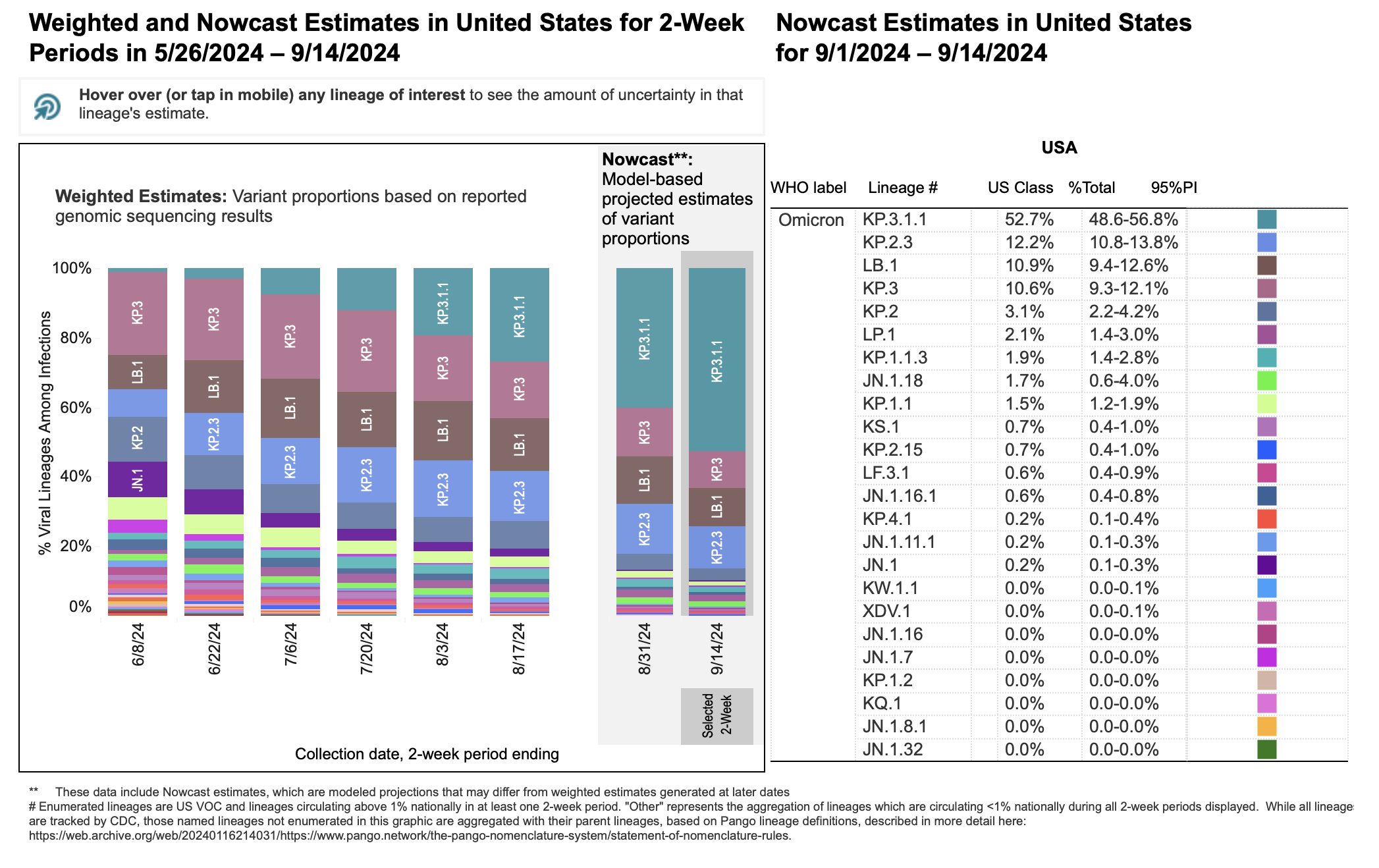

As of September 17, 2024, the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants KP.2, KP.2.3, KP.3 and KP.3.1.1, as well as LB.1, have high prevalence in the United States. CDC Nowcast projections estimate KP.3.1.1 to account for approximately 53% of new COVID-19 illnesses in the US. As of September 17, the estimated percentage of illnesses caused by KP.2.3 is 12.2% (a slight decrease from the previous four-week period), and the estimated percentage of illnesses caused by LB.1 is 10.0% (also a slight decrease from the previous four-week period).

Pictured above is a figure showing recent emergence of KP.2, KP.3, LB.1, KP.3.1.1, and other Omicron strains in the U.S. For additional infographics depicting the change in variant proportions in the U.S. over time and/or geographically or phylogenetically, visit the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker resource.

Variant nomenclature

Several emerging variants have been given specific names according to the mutations at key sites in the spike protein. So-called “FLip” variants possess mutations L for F at site 455, and F for L at site 456, in the backbone of XBB.1.5. An additional strain called “SLip" has also emerged, which has a JN.1 spike protein with an F for L at site 456 mutation; the “S” in “SLip" refers to the L for S at site 455 mutation characterizing JN.1. Finally, “FLiRT” variants are so named because they exhibit the mutations F for L at position 456, and R for T at position 346. The emerging strains KP.2, KP.3, and LB.1 are all considered to be in the family of “FLiRT” variants; this also includes descendants such as KP.2.3 and KP.3.1.1.

Some FLiRT variants exhibit a deletion (S:S31del) in addition to the substitutions present in KP.2 and KP.3. Variants with this deletion, such as LB.1, may sometimes be referred to as “deFLiRT,” indicating that the variant has the same mutations as other FLiRT variants with this additional deletion.

Immunity, Transmissibility and Vaccines: Last Updated September 17, 2024

Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron-specific antibodies

A very high proportion (>95%) of individuals currently have identifiable antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, either from infection or immunization or a combination of both. A recent large serosurvey aimed at investigating mucosal immunity in the Netherlands also identified very high (95%) spike-specific IgG in nasal samples of individuals.

Existing research in the U.S. indicates a large increase in SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence from the pre-Omicron to Omicron era, across all age groups; it was estimated that by the third quarter of 2022, approximately two-thirds of individuals aged 16 years and older had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, with approximately half of individuals having hybrid immunity.

KP.3.1.1-specific immunity and transmissibility

The KP.3.1.1 variant is a descendant of the KP.3 variant (itself a descendant of JN.1) contains several mutations associated with escape from vaccine-mediated immune protection. Preliminary evidence (not yet peer-reviewed) suggests that the emerging KP.3.1.1 variant may exhibit higher infectivity compared to KP.3, and that 50% neutralization titers against KP.3.1.1 are significantly lower than KP.3 in convalescent sera. Additional evidence (not yet peer-reviewed) corroborates the findings that KP.3.1.1 has increased infectivity relative to JN.1 and elicits reduced neutralizing antibody relative to JN.1.

Other KP.2- and KP.3-specific immunity and transmissibility

The KP.2 variant (also called JN.1.11.1.2) is a descendant of the JN.1 variant and contains several mutations that are associated with escape from vaccine-mediated immune protection. Preliminary research suggests that the estimated relative effective reproduction number of KP.2 (Re) may be 1.22 times higher than the Re for JN.1. An additional variant, KP.3, is believed to have similar virological and epidemiological characteristics to KP.2. A third emerging variant, LB.1, is also a FLiRT variant.

Preliminary findings suggest higher viral fitness for KP.2 and KP.3 than prior JN.1 variants and subvariants, although a pseudovirus assay in this research suggested that the infectivity of KP.2 may be 10.5-fold lower than JN.1. Importantly, in virus neutralization assays, KP.2 showed substantial resistance to sera of individuals vaccinated with monovalent XBB.1.5 (i.e., the most recently updated COVID-19 vaccine). However, because of the high antigenic similarity between KP.2 and JN.1, it is expected that individuals with a recent JN.1 infection will likely have some cross-neutralizing antibody protection against KP.2.

LB.1-specific immunity and transmissibility

Like KP.2 and KP.3, LB.1 is a descendent of the JN.1 variant. Unlike KP.2 and KP.3, however, LB.1 exhibits an additional mutation (S:S31del) in addition to the substitutions present in KP.2 and KP.3 that designate them as ‘FLiRT’ variants.

Preliminary results from a modeling study that has not yet been peer-reviewed, from a research group at the University of Tokyo, indicate that the relative effective reproduction number (Reff) of LB.1 may be higher than KP.2 and KP.3. An additional subvariant, KP.2.3, exhibits the same mutation (S:S31del) as LB.1. It also exhibited a higher relative Reff compared to KP.2 and KP.3 in the same study.

This study also conducted neutralization assays using breakthrough infection sera with XBB.1.5, EG.5, HK.3, and JN.1 infections as well as infection-naïve, monovalent XBB.1.5-vaccinated sera. In all four groups of sera, both LB.1 and KP.2.3 were found to have lower 50% neutralization titers compared to JN.1 and KP.2. Importantly, infection-naïve XBB.1.5-vaccinated sera had very low neutralization titers against JN.1 subvariants, and titer values were lower for KP.3, LB.1, and KP.2.3 compared to JN.1.

Taken together, these results suggest that the potential for infection with an emerging variant of Omicron is substantial, even for individuals who have received the most recent COVID-19 vaccine updates. It appears that LB.1 and KP.2.3 exhibit higher infectivity and greater immune escape than KP.2 and KP.3.

JN.1-specific immunity and transmissibility

The JN.1 variant is a subvariant of Omicron variant BA.2.86 and contains several mutations that are associated with escape from vaccine-mediated immune protection. Emerging variants KP.2, KP.3, and LB.1 are descended from JN.1.

The JN.1 variant is antigenically distinct from the XBB.1.5 variant, which is the current target of monovalent COVID-19 vaccines. Recent research shows that JN.1 is very efficient at immune evasion (even more so than other Omicron variants), resulting in an increased reproductive number. Evidence from a small serological study has suggested that serological protection against SARS-CoV-2 is reduced against JN.1 variants compared to other BA.2.86 viruses, among young adults who had received at least a complete primary series of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Additionally, a recent serological survey of 1,472 community-dwelling individuals found that although a majority of previously infected individuals had antibodies with neutralizing activity against JN.1, the neutralizing capacity was relatively low compared to neutralizing capacity against other SARS-CoV-2 strains. These findings are supported by an additional antigenic cartography analysis, which indicates that although XBB.1.5 booster sera was capable of neutralizing XBB sublineage variants (including JN.1), a five-fold titer difference was still observed.

Although JN.1 does appear to be more transmissible, it does not appear to cause more severe disease than other SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Vaccines and current SARS-CoV-2 variants

Vaccination is still effective in preventing severe COVID-19, and vaccination with up-to-date SARS-CoV-2 vaccines does produce antibodies that can recognize JN.1 and its descendants.

Research has identified that JN.1 is resistant to monovalent XBB.1.5 vaccine sera, although data also suggest that JN.1 is unlikely to completely evade T-cell recognition. A recent report has identified substantially higher neutralizing antibodies elicited by bivalent (ancestral strain plus BA.4/BA.5) vaccines against several Omicron subvariants, including BA.2.86 and JN.1, compared to the original monovalent vaccine. There is very limited evidence to estimate neutralizing capacity of current vaccine-elicited antibody against KP.2 and KP.3 strains. However, preliminary evidence suggests that KP.2 and KP.3 (as well as other related FLiRT variants) may exhibit additional immune evasion capacity beyond JN.1; additionally, preliminary evidence (not yet peer reviewed) suggests that emerging variants LB.1 and KP.2.3 may exhibit additional immune evasion beyond what is exhibited by KP.2 and KP.3.

Preliminary estimates of vaccine effectiveness against disease likely caused by JN.1 are imprecise due to the recent emergence of JN.1 in the United States and the subsequent rapid rise of FLiRT variants taking its place. Although preliminary estimates suggest that there is still substantial VE against JN.1 (VE: 49%; 95% confidence interval: 19% – 68%), the VE estimate is lower than the estimate against non-JN.1 illnesses (VE: 60%; 95% confidence interval: 35% – 75%). These U.S.-based estimates for XBB.1.5 vaccine effectiveness against JN.1 were similar to preliminary estimates from a recent preprint using data from the Netherlands (41% VE in 18-to-59-year-olds and 50% in 60-to-85-year-olds). However, estimates for JN.1-specific vaccine effectiveness were lower in a large vaccine effectiveness study of Cleveland Clinic employees (19% VE). There is very limited evidence to estimate effectiveness of current vaccines against KP.2, KP.3, and LB.1. However, the effectiveness of current vaccines against these emerging variants is likely to be lower than against JN.1 given the additional immune escape properties exhibited by these variants that have been identified in recent research (not yet peer reviewed).

Due to these combined factors, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended in late February 2024 that people 65 years of age and older should get an additional updated COVID-19 vaccine in spring 2024. Additionally, FDA’s Vaccines and Biological Products Advisory Committee and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended in June 2024 that COVID-19 vaccines for fall/winter 2024-2025 should be monovalent vaccines with a JN.1-specific antigen.

Diagnostic Capacity for Variants: Last Updated September 17, 2024

Limited evidence available suggests that COVID-19 antigen and PCR tests are still capable of identifying recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 variants, such as XBB.1.5, EG.5.1, JN.1, KP.2, KP.3 and FLiRT variants. Reduction or failure of the spike gene amplification in RT-PCR can be used as a (time-dependent) proxy indicator of JN.1 (versus other Omicron lineages) infection. It is important to note that most rapid antigen tests identify the presence of nucleocapsid (N) protein; therefore, changes in spike (S) protein are not expected to affect test performance. Similarly, PCR-based tests are regularly monitored by clinical laboratories for testing performance; many PCR tests identify both N and S protein, allowing these tests to also be resilient to changes that may occur in S protein with emerging variants.

As with prior SARS-CoV-2 variants, rapid antigen tests may not perform as well as PCR for individuals with low viral load, and/or individuals who may be asymptomatic. (For more information on comparative test performance between PCR and rapid antigen tests, refer to this IDSA resource.)

Therapeutics: Last Updated September 17, 2024

Paxlovid continues to be effective against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, including JN.1 and FLiRT variants. Paxlovid is a protease inhibitor; its mechanism of action involves a part of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that is not related to the spike protein. It is therefore hoped that additional potential changes to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 variants will not affect the effectiveness of Paxlovid.

Preliminary evidence (not yet peer-reviewed) suggests that Pemgarda (pemivibart) may be less active against recent JN.1 sublineages, specifically FLiRT variants with Q493E and S31-deletion mutations. Primarily, this includes KP.3.1.1.